Topic DS: How to prove things with Sentential logic

1 Derivations in sentential logic

Now you will learn how to make

derivations

in sentential logic.

A derivation displays step by step reasoning from premises

to conclusion. Each step along the way follows the rules.

The sort of system of rules you will study is often called

a

natural deduction

system because it is somewhat like the

way people actually deduce conclusions from premises. It

isn't really natural---it is an artificial, formal

system---

but a natural deduction system can be easier to use and

understand than other available methods.

1.1 An example derivation

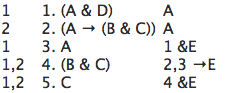

Here is an example of a derivation in our system:

This example shows, step by step, that "C" follows

from "(A & D)" together with "(A → (B & C))".

That is, starting with "(A & D)" and "(A → (B &

C))"

one can reach the conclusion "C" by following the

rules of the system. In short, "C" is

derivable

in our system from "(A & D)" and "(A → (B & C))".

In symbols:

(A & D), (A → (B & C)) ![]() C

C

The symbol "![]() "

is sometimes called the "turnstile".

"

is sometimes called the "turnstile".

We will use it to mean that the formula on the right

is derivable in our natural deduction system from

the formulas, if any, on the left.

1.2 The parts of a derivation

Let's examine the sample derivation in detail.

The middle column is a numbered list of well-formed

formulas of sentential logic. This is the heart of the

derivation. Each formula in the list is numbered.

In this case there are five formulas, numbered

from 1 to 5.

The right column tells us what rule is followed.

In this derivation three different rules are used.

In line 1 "(A & D)" was written down by Rule A,

the Rule of Assumption. The Rule of Assumption

is also used on line 2. On lines 3 and 5 Rule &E

is followed, and line 4 employs rule →E. There are

twelve different rules in all in our system.

The left column contains a list of zero or more

dependencies.

For example, line 1 depends on line 1,

and line 5 depends on lines 1 and 2. We'll see more

about what the dependencies mean as we go along.

In short, at each step in making a derivation you

write down three things: a formula (with a line number),

a note on the right saying which rule you have applied,

and, on the left, a list of dependencies (if any).

1.3

Three rules

You

have just seen three rules in action. Let us see

more precisely how to use each of these three rules.

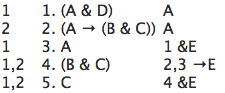

The

Rule of Assumption

says that you can write

down any well-formed formula of SL you like.

The dependency is that formula itself.

For example, we just saw this rule used twice:

![]()

It may seem odd to be able to write down any formula

you want at any time. But that does not mean you can

derive anything at all. The rule does not merely say you

can write down any formula. The rule says that you can

write down any formula

depending on itself.

In effect, for any formula φ,

the rule lets you say that

φ

follows from itself; φ

is derivable from itself.

In this case, for example, line 1 means that "(A & D)"

is derivable from "(A & D)":

(A & D) ![]() (A & D)

(A & D)

And line 2 means that "(A → (B & C))" is derivable

from "(A → (B & C))":

(A → (B & C)) ![]() (A → (B & C))

(A → (B & C))

The

& Elimination Rule,

&E, says that if you have

a line which is a conjunction you can write down

either of the conjuncts. In other words, if you

have a line (φ&ψ),

you can write down φ

or ψ.

The new line depends on everything the conjunction

depends on.

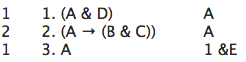

That rule is used at line 3 of the sample derivation:

One can use &E to write down "A" at line 3 because

line 1 is a conjunction, "(A & D)". Line 3 depends on

everything line 1 depends on. Line 1 depends only

on line 1. So line 3 depends only on line 1.

The annotation on the right says that you applied

&E to line 1.

The →

Elimination Rule,

→E, says that you can

write down ψ

if you have a line (φ→ψ)

and another line φ.

The

new formula ψ

depends on everything that (φ→ψ)

depends

on, together with everything that φ

depends on.

This rule is commonly called

Modus Ponens.

But we call it the →

Elimination Rule

to emphasize the

similarity between this and other elimination rules,

such as &E. Using an elimination rule, one writes down

part of an earlier formula. So elimination rules let one

move from longer formulas to shorter formulas.

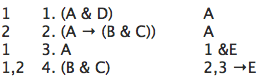

→E is used at line 4 of the sample derivation:

In this case, we have "A" on line 3,

and "(A → (B & C))" on line 2, so we can

write down "(B & C)", depending on

everything line 2 and line 3 depend on.

1.4

Practice Exercises

Now you have seen 3 rules: &E, →E, and A.

It is time to prove some things yourself!

Make derivations to show the following,

using only these 3 rules, if you can.

Try not to look at the answers

until you have finished your derivation,

or have decided that it can't be done.

Exercise

1.4a

Show the following using only &E, →E, and A.

(A & B) ![]() A

A

((A

∨

B) & (B→A)) ![]() A

A

(A

→ (B & C)), A ![]() B

B

A,

B ![]() (A

&

B)

(A

&

B)

A,

(A → (B → (C → (D → (E → F))))) ![]() F

F