Qing (Reality, Feelings)

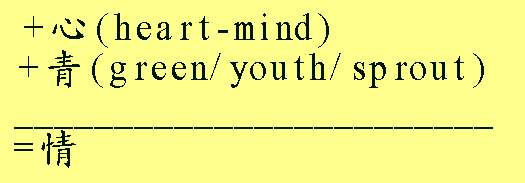

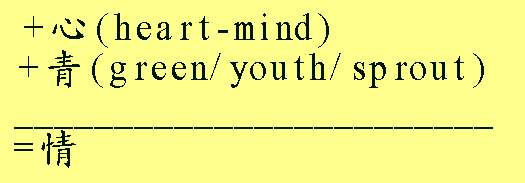

Standard dictionary entries give two puzzling equivalents for qing: 1) affections, feelings, emotions and 2) facts, circumstances, reality. Both contribute to a large number of compound phrases. We find the emotion-linked "love letter" and "sentiments" alongside the fact-linked "truth" and "reason." The character consists of a heart semantic and a qing (color of living nature-green/blue-hence young, growing etc.) phonetic. We find the phonetic in other complex characters with the sense of "pure" "clean" and "clear". Classically it was linked phonetically with "request, please!" which uses a language semantic with the same qing phonetic.

I will here develop the hypothesis that in early China, the character referred to input from the world that is relevant to following a guide (a dao). The writers implicitly contrasted qing with conventions-the guidance complement. Thus, we can explain both the 'reality' and the 'sentiment' uses as emerging from the conception of the pre-social inputs we use to guide our behavior according to social guides.

Confucius' Analects used the character only twice in contexts that suggest a contrast and complementary relation to ritual morality. "If those above favor reliability, then the no one will fail to use qing." (Analects 13:4) Mozi develops a political role for the concept and emphasized the contrast between natural or self-nurtured qing versus conventions or ritual. According with the qing of those below marks a well-ordered society (government). The ideal type of harmony is that between the heart qing (from below) and the language qing (from above). Guidance requests harmonize with the people's natural reactions in the real world. When guidance precisely maps onto the qing of those below, they will desire things like benevolence and morality.

Mozi's formulated a utilitarian moral theory so interpreters took his qing to be a subjective measure of utility-pleasure or happiness. Generally, however, Mozi explained utility in real, material terms-actual well being. That he did link moral utilitarianism with qing suggests that the sense of the character was still mainly objective reality. For Mozi, it was important to distinguish between qing and wei (artifice).

Mozi's best known theoretical use of qing was in his theory of language. He argued that among the measures of correct language use was "Its according with the qing of the people's eyes and ears." He spells out this accord in two key arguments-whether they say "have" or "lack" of spirits and fate. The other tests of language are a use test (pragmatic) and a historical test (conventions). Mozi assumes that all three tests favor utilitarian grounds for guiding language use. He does not explore the possibility that the standards might pull in other directions.

Mencius' intuitive moral theory postulates a natural, pre-social guidance scheme. He does not use qing to refer to this moral content, though his later interpreters did. He preferred using xing, which also attaches a heart semantic to a sheng (life) phonetic. Presumably he wants to distinguish a growing, maturing, systematic moral sensibility from the piecemeal natural inputs into the heart. Qing itself continues to serve Mencius as a reality-concept that is relevant to guidance.

Laozi's Daode Jing conversely, totally forgoes qing in favor of yu (desire)-a term with which qing was later frequently combined. Perhaps his motive was to suggest that desires are products of socialization while qing are not. In the process of learning language itself, this analysis suggests, we learn distinctions and acquire new desires guided by the learned distinctions. This socialization pulls us unconsciously away from our spontaneous nature. Like Mencius, supposedly, Laozi regards spontaneous nature as good. His strategy for avoiding this socially guided departure from natural behavior was "forgetting" language and socialization.

Though Laozi did not use qing in developing his position, it was assumed in subsequent developments. Other philosophers took up and developed the insight that learning a language instills a kind of unnatural prejudice in our attitudes and, consequently, in our behavior. The most famous and sophisticated of these was Zhuangzi. He accepted the Later Mohists' proof that we could not coherently conclude that we should abandon language. Instead, Zhuangzi emphasized a kind of pluralism. He encouraged us to recognize that different languages, conventions, lives, even various species produce divergent guiding views. All base their guidance on conflicting standards of justification and interpretation.

Zhuangzi's usage was important in forcing interpreters to notice the 'reality' implications of the character. In many passages he uses it where it can hardly be intelligible as feelings. Still, qing clearly retains a prescriptive role in The Zhuangzi. At one point, the text gives the conventional list of what we have come to regard as qing-happiness, anger, sorrow, pleasure, fear and regret. He does not call them qing but goes on to wonder, Hume-like, if we have any qing of something (a self?) that links them all together. Without them, he notes, there would be no "me" and neither choosing nor objects to be chosen. However, when I seek for a "true ruler" of them, I do not find it's qing.

Zhuangzi most famously pairs qing with xing (shape). Both are givens for purposes of guidance, but the content of qing is comparatively amorphous. In a famous (and interpretively controversial) passage, Zhuangzi debates with Hui Shi about qing. Zhuangzi's conclusion (on one parsing) is that qing inputs are pro-con judgments (shi-fei) and his advice to lack qing amounts to his saying, "Do not let such judgments harm yourself or multiply excessively." Our shape is given in life, but our "self" is a product of judgments. However, we should each monitor the development of these, not surrender them to the manipulation of social authority. Pre-social Qing are positive elements, for Zhuangzi.

The strongest early negative views on qing emerged in the writing of Xunzi. There is a tension in Xunzi's use of qing. In general philosophy, he seems to assume that li (ritual) can shape and control qing. (This is consistent with Laozi's theory of yu (desires).) The novel point is Xunzi's argument from political-economy that we should welcome such social control. He suggests that use of li (ritual) to control desires is how society can achieve "equal" fulfillment in conditions of material scarcity. Ideally, lower classes will have tastes and desires for things that are plentiful and only high officials will cultivate tastes for things that are relatively rare-and not for the coarse and common things. In these contexts, his attitude to qing reflects a view of their malleability.

However, in other sections, the text treats qing as a more purely negative source of disorder. Qing anchors his famous argument that human nature is evil. He vociferously attacks the philosopher Sung Hsing for his view that the qing desires are few. On its face, however, Song Hsing's theory resembles that of Laozi. Most desires are socialized; the reality based (pre-social or natural) desires are few. This could anchor an attack on Xunzi's position since it suggests that conventions like li (ritual) create unnecessary desires. They, thus, generate competition and strife. Xunzi would want to insist that li (ritual) is essential for order, not the cause of the disorder.

In these sections, Xunzi specifies that qing and desires are initially limitless in their range and content. We cannot control the desire itself, but we can control our "seeking" behavior. This analysis is at odds with the political-economy argument because it implies that in any well ordered society, we will not satisfy most of our natural desires. Citizens will be "repressed" by conventions so they do not act on their desires. Xunzi, here, assigns the name qing to the canonical list of emotions-like, dislike, happiness, anger, sorrow, and pleasure.

Xunzi bequeathed his attitudes toward qing to the emerging Confucian orthodoxy in the Han. Dong Zhongshu linked qing to the classical dualism of yin and yang. The qing were evaluated as the "evil" yin (female) and xing (moral nature) as the good yang (male). Qing became a generalized reference to the mechanism of human evil. This analysis underwrote the negative view of qing that helped it mesh with Buddhism. That implication dominated the residual 'reality' component in post-Buddhist Confucianism.

Buddhism introduced into the Chinese intellectual world a Western "folk psychology" complete with the contrast of beliefs and desires. Moreover, at the initial or introductory level, Buddhism used desire to explain evil or suffering. Salvation or enlightenment consists in overcoming desire. The Buddhist goal is individualized in comparison to the social-political stance of the classical Chinese thinkers, and the notion of qing was almost exclusively linked to individual psychological states. The esoteric or advanced teachings often take back this initial simple, dualistic stance, but Buddhism cements the subjectivist component of qing firmly in Chinese consciousness

Some of the dual nature re-emerges in orthodox Neo-Confucianism. Qing themselves, as long as they are not one's own but a reflections or accurate viewpoints of the qing of things themselves, may be orderly. So the orthodox versions of the theory often modify qing by 'human' or 'things'. They do speak of Mencius' responses of the heart as qing, and insist that the heart's qing are metaphysically in accord with the moral structure of the cosmos. They contrast this with "human qing" or "selfish qing."

The distinction, in general, between a "human" and a "dao" heart-mind is one target of the School of Mind's attack on Zhuxi's orthodoxy. Wang Yang-ming, the dominant theorist of the Mind School, denied that even natural, subjective qing were inherently evil. He analyzed them as functions of innate knowledge (inherently good) and thus prior to good and evil. They still explain evil, for example when they are "attached" to things (have a thing-content) because in that case they become "grasping" or "selfish." If we recognize and "realize" their source in innate good knowledge, we class them as orderly and good. If our qing are spontaneous responses, without calculation, that arise from our contact with the world, then our responses should be good ones. This direction of Neo-Confucian thought led to an incipient utilitarianism immediately preceding and during China's modern contact with the West.

Glossary

|

Ching |

情 |

Reality, facts, feelings, passion |

|

|

性 |

Nature, disposition, attribute, moral nature |

|

|

形 |

shape |

|

Li |

禮 |

Ritual, convention, propriety |

|

Sheng |

生 |

Life, birth, grow |

|

Dao |

道 |

way, guide, discourse |

|

Yang |

陽 |

Male principle, warm, sun, light |

|

Yin |

陰 |

Female principle, dark, damp, cold |

|

Yu |

欲 |

desire |

Bibliography

Chan, Wing tsit. 1963 A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy (Princeton: Princeton University Press) .

Chan, Wing tsit. 1986 Neo-Confucian Terms Explained (New York: Columbia University Press) pp. xi-277.

Cua, Anthony S.. 1985 Ethical Argumentation: A Study in Hsunzi's Moral Epistemology (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press) .

Graham, Angus. 1989 Disputers of the Dao: Philosophical Argument in Ancient China (La Salle, IL: Open Court) .

Hansen, Chad. 1992 A Daoist Theory of Chinese Thought (New York: Oxford University Press) pp. xv-448.

Hansen, Chad. 12/30/95 "Qing (Emotions) in Pre-Buddhist Chinese Thought," in Joel Marks and Roger T. Ames (ed.), Emotions in Asian Thought (State University of New York Press) pp. 181-211.

Munro, Donald J.. 1969 The Concept of Man in Early China (Stanford: Stanford University Press) .

Wu, Yi. 1986 Chinese Philosophical Terms (Lanham, MD: University Press of America) .