ROUSSEAU–ENEMY OR REFORMER OF THE ARTS?

THE CASE OF MUSIC

Rousseau’s music background:

The young Rousseau

taught himself music while holding various posts as a music teacher, and

performing at home (a common practice). “I certainly must have been born for

this art [of music], for I began to love it in my childhood, and it is the only

one I have loved constantly throughout my life” (Confs. V, 175).[1]

At Les Charmettes he avidly read Rameau’s Traité

de l’harmonie while convalescing from an illness (Confs. V, O.C. I, 184).[2]

Rousseau devoted himself to music

appreciation in opera houses and churches during his stay in

Rousseau’s cultivation

of this and other arts and sciences (e.g. chemistry and botany) may cause us to

wonder if his Discourse on the Sciences

and the Arts is hypocritical. Rousseau

himself argued throughout his works that one way of life suits a morally pure

people, e.g. the Spartans, while another suits decadent peoples, e.g. the

French. He could therefore maintain that

music, the product of leisure, luxury and vanity, can nevertheless serve a

useful moral and political function in decadent societies. His advocacy of Italian music (see below)

exemplifies this view.

Reformer of Musical

Notation:

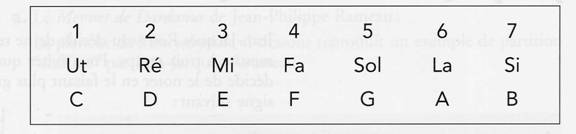

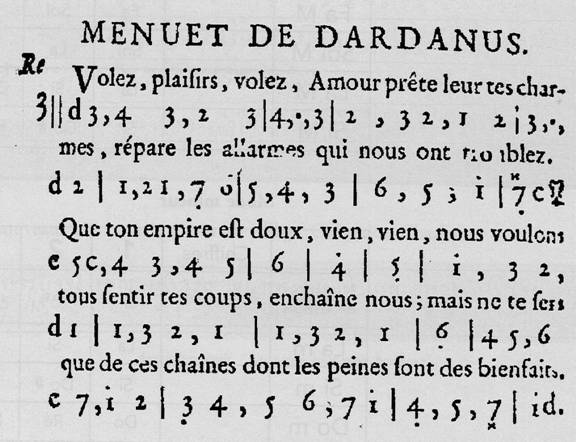

1742: Rousseau’s Projet concernant de nouveaux signes pour la

musique and Dissertation sur la

Musique moderne presented a novel scheme of musical notation, with the hope

of reforming a difficult and imperfect system (O.C. V, 167).[3]

The great naturalist

Réaumur introduced Rousseau and his scheme to the Royal Academy of Sciences:

“The paper was a success, and brought me compliments that surprised me as much

as they flattered me, for I hardly imagined that in the eyes of an Academy,

anyone who was not a member would appear to possess even common sense…. But not

one of them knew enough about music to be capable of judging my scheme” (Confs. VII, 267). According to D’Alembert, the reluctance to

adopt Rousseau’s notation system was the result of a “prejudice in favor of the

older one” (PD, 133).[4]

The Opera Composer,

Critic and Bouffon:

1745: Rousseau’s

operatic ballet, Les Muses Galantes:

Jean-Phillippe Rameau

(1683-1764), criticized the work as too good to have been composed by an

amateur; Rameau, a composer and music theorist of renown, is especially

well-known for his harmonic theory, the basis for music theory to this day.

(Rameau is the uncle in Diderot’s novel, Rameau’s Nephew.)

The Querelle des bouffons [war of the opera

fans]:

1752: Rousseau becomes

the leader of the “Bouffons,” fans of Italian opera (opera buffa, e.g. Don Giovanni, the Barber of Seville), who ranged

themselves against the fans of French opera, in the Querelle des bouffons. This was no merely diverting artistic controversy,

however; under Rousseau’s influence, it took on distinct moral and political

implications. French opera was formal,

rule-bound and traditional; it exemplified Cartesian principles of mathematical

precision, unity and order. French opera

reflected the taste of the Court for portrayals of heroic themes, while Italian

opera was less rigidly structured, more melodic, less conventional and

portrayed common people and their ordinary predicaments. Italian opera was

therefore an opera of the people – a democratic opera – while French opera was

Court opera. In Italian opera Rousseau

saw the potential to conjure up feeling (“sentiment”) through music, to express

the principles of virtue nature has engraved on the human heart (see end of

first Discours).

Prominent

Encyclopedists sided with Rousseau in seeing Italian opera as representative of

political and moral progress. D’Alembert argued that “freedom in music implies

freedom to feel, and freedom to feel implies freedom to act, and freedom to act

meant the ruin of states…let us put a brake on singing if we do not wish to

have liberty in speaking to follow soon afterwards.”[5]

This is not to say that they felt

compelled to reject Rameau and his harmonic theory (see below).

1752/3: Le Devin du Village [The Village

Soothsayer]:

A comic opera in the

Italian style, but in the French language, it was a huge success. It told the story

of two peasant lovers split apart by an aristocratic interloper, but later

reunited. Despite its Italian style, it

was performed before the King and Court at Fontainbleau, and later at the Paris

Opéra. According to Rousseau’s contact at Court, the King could not “stop

singing in the vilest voice in his whole Kingdom: ‘I have lost my serving man;

all my joy has gone from me’” (Confs.

VIII, 355). Audiences praised the

opera’s simplicity and charm. Rousseau claimed the opera “was in an absolutely

new style, to which people’s ears were unaccustomed.” Its novelty lay in the relationship of the

music to the words: “The part to which I had paid the greatest attention, and

in which I had made the greatest departure form the beaten track, was the

recitative. Mine was stressed in an entirely new way, and timed to the speaking

of the words” (Confs. VIII, 350).

1753: Lettre sur la musique françoise [Letter on

French Music]

In this polemic

Rousseau criticized French music, writing in the opening paragraph: “before

speaking of the excellence of our [i.e. French] Music, it would perhaps be good

to assure ourselves of its existence, and to examine first, not whether it is

[made] of gold, but whether we have one [at all]” (O.C. V, 291). Such words

were not music to the ears of Rameau, who bestowed his undying enmity on the

Genevan upstart who dared to take French music to task as “our Music.”

Rousseau held up

Italian music as the model. His reasoning is complex: the differences among

national styles of music are founded in the melody, more particularly in the

“prosody” of the language (O.C. V,

294), while harmony is the same for all nations (O.C. V, 292). Italian is the

language most suited to music, as it is “sweet, sonorous, harmonious and

accented more than any other, and these four qualities are precisely those most

suitable to song” (O.C. V, 297). French is a guttural language ill-suited to melody.

Rousseau details a series of remarkable experiments

he claims to have performed to determine which language “contains the best form

of music in itself” (O.C. V, 299). He observed an Armenian with no prior

experience of music listening to examples of Italian and French song; the

French song evoked surprise rather than pleasure, while the Italian song

brought a response of enchantment.

The Lettre launched a controversy that

overshadowed the dissolution of the parlements:

“Whoever reads that this pamphlet probably prevented a revolution in

1753/4: L’Origine de la Mélodie [The Origin

of Melody] (first published in 1974)

This the

“epistemological pivot” of Rousseau’s musical theory (editor’s introduction; O.C. V, cclxxiv). In it Rousseau argues that music and language

have a common origin, more specifically, that melody is the essence of a music

based in nature: “Melody or song, the pure work of nature, owes its origin…not

to harmony, work and production of art….” Melody is composed of accent and

rhythm; it alone transmits sentiments (O.C.

V, 337). Melody is born with language;

the poverty of early languages enriched melody, in that song took on greater

expressiveness in lieu of words (O.C.

V, 333). Thus, “…speech is the art of

transmitting ideas, melody is that of transmitting sentiments….” (O.C. V, 337). Music that does not express human feelings is

but a sterile, mathematical exercise.

1754? (date

uncertain): Essai sur l’origine des

langues, où il est parlé de la mélodie et de l’imitaion musicale [Essay on the

origin of languages, in which melody and musical imitation are discussed]

This work was originally planned as part of the Discours sur l’origine de l’inégalité,

but Rousseau considered it too long and out of place to be included in that

work. The Essai expands significantly

on the argument that the formation of language marks a crucial juncture in

human history. Passions, not needs, form the basis for language: “We begin not by

reasoning but by feeling. People

maintain that men invented language to express their needs; this opinion seems

to me indefensible” (V, 380; cf. Basic

Writings, 62). Rousseau’s position

has been summarized with this word play on Descartes’s cogito: “Je sens, donc

je suis [I feel, therefore I am].” Rousseau dismisses the argument that human

language has a physiological basis; even though animals have organs of speech, they

do not speak “the language of convention” as do humans. Human language is possible due to a particular

faculty unique to our species.

At the end of the Essai

Rousseau turns to the relevance of his argument for political philosophy. In Antiquity language was the medium of

communication between the leaders and the assembled people of a free city (

Popular languages have become to

us as perfectly useless as eloquence.

Societies have taken their final form; nothing will be changed except

with the cannon and with ecus [money], as there is nothing more to say to the

people except, give money, it is said

with placards on the street corners or with soldiers [quartered] in houses; it

is not necessary to assemble anyone for that: on the contrary, it is necessary

to keep the subjects apart; this is the first maxim of modern politics.

There

are languages favorable to liberty; these are sonorous, prosodic,

harmonious….Ours are made for whispering at Divans [the couches of absolute

rulers]. Our preachers torment

themselves, work themselves into a sweat in the temples, without knowing

anything about what they say (O.C. V,

428).

1749: Articles on music in the Encyclopédie (390 in all) (see PD,

133):

In expressing his views on such matters as melody and

harmony, Rousseau angered the great Rameau, who attacked Rousseau in Erreurs sur la Musique dans l’ Encyclopédie.

D’Alembert, author of some articles on music, along with Diderot and other philosophes, rose to Rousseau’s defense.

The dispute largely resulted from Rameau’s rage at Rousseau’s polemic of 1753,

for the Encyclopédie actually

supported Rameau’s theories in large part.

1768: Dictionnaire

de musique (composed 1749-1764):

Lengthy work of exposition, clarification and

criticism (O.C. V, 605-1154): “Music

is, of all the beaux Arts, that which

has the most extensive Vocabulary, and … as a result, the most useful [one]”

(O.C. V, 605). It is based on the Encyclopédie articles, but much

reworked: “they [the Encyclopédie’s

editors] gave me only three months to [write the articles], and three years

would have been required for me merely to read, extract compare and compile the

Authors I needed: but the zeal of friendship blinded me to the impossibility of

success” (O.C. V, 605). “Wounded by

the imperfection of my articles…I resolved to recast the whole…and to make a

separate treatise at my leisure with more care” (O.C. V, 606).

Postscript:

Rousseau left a significant body of work on music

philosophy and theory. He was involved

in the most heated musical debates of his day, and composed an opera that

expressed his theoretical position, albeit in French lyrics. This opera is available on CD and is still

performed from time to time, e.g. in

Rousseau worked as a music copyist to earn his living

until near the end of his life.