(This article was written in 1996 in the mistaken belief that it had been commissioned for the Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The conventional and much repeated view that Condillac simply ‘naturalized’ British Empiricism in France is mistaken (see the ‘brief outline’ and the last six paragraphs of the section about his thought. The text was somewhat amended in 2013 and 2017.)

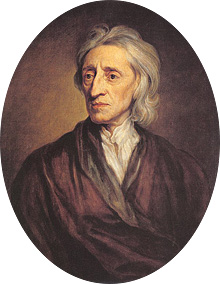

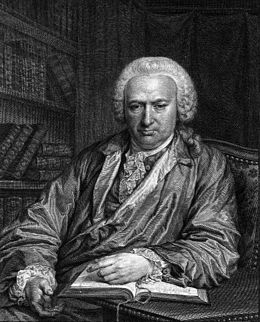

Condillac was a major but independent figure of Enlightenment France. His first book was subtitled “a supplement to Mr Locke’s Essay on Human Understanding”, and he has often been depicted as the thinker who brought British Empiricism to France. However, he differed from Locke in several crucial ways.

First, he claimed that all mental operations could be derived from sensation alone, rejecting Locke’s view that ‘reflection’ is a source of ideas.

Second, he took Locke’s attack on innate ideas a major step further, by denying the existence of any innate faculties. Mental faculties too (e.g. attention and memory) were themselves generated from the occurrence of simple sensations.

Third, where Locke claimed that the function of language was to communicate ideas which could exist independently of it, Condillac insisted that the function of language was constitutive in their formation.

This claim culminated in the view that knowledge itself is a well-made language, and that the basic form of a well-made language is algebra, which consists of tautological propositions.

Condillac influenced the encyclopedists in his own time, and the idéologues after him. Nevertheless, Condillac’s ‘empiricism’ is given a new look by his putting forward an early form of finitism in mathematics. The metaphysical implications of this were already prefigured in one of his earliest treatises, published anonymously and never acknowledged by him, in which he gave an a priori argument for the existence of ‘monads’.

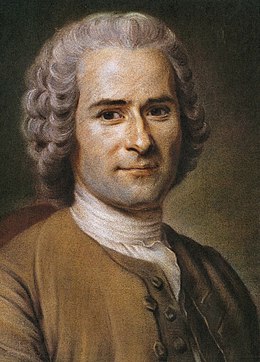

Étienne Bonnot was born in Grenoble in 1714, and belonged to a family of lawyers. He took the name Condillac from a family estate at the death of his father. Rousseau was tutor to his elder brother, and from this came a friendship between Rousseau and Condillac. He was ordained priest in 1741, but it seems that he did not pursue the sacerdotal office. In Paris, his circle included the encyclopedists Diderot and d’Alembert. Though it appears that he did not directly contribute articles to the Encyclopédie, some of its entries are textually very close to what Condillac himself had written.

His first fame was earned with the publication of his Essai sur l’origine des connaissances humaines (‘Essay on the Origin of Human Knowledge’) in 1746. In the following year, his prize essay Les Monades (‘Monads’) was published anonymously in the proceedings of the Academy of Berlin, of which he was made an associate member in 1749, the year in which he published his Traité des systèmes (‘Treatise on Systems’). There followed the Traité des sensations (‘Treatise on Sensations’) in 1754, and the Traité des animaux (‘Treatise on Animals’) in 1755. In 1758, he was appointed tutor to Prince Ferdinand of Parma (grandson of Louis XV), a post which he held for nine years, and which resulted in the eventual publication in 1775 of his Cours d’études pour l’instruction du prince de Parme (‘Course of Studies for the Instruction of the Prince of Parma’) in 16 volumes covering a variety of subjects. On his return to France, he was made an abbé in 1765, and a member of the Académie française in 1768. He published Le Commerce et le gouvernement considérés relativement l’un à l’autre (‘Commerce and Government considered in relation to each other’) in 1776, and in 1780 La Logique ou les premiers développements de l’art de penser (‘Logic, or the first development of the art of thinking’). He was working on a comprehensive edition of his works, and on a further work, La Langue des calculs (‘The Language of Calculation’), when he died in 1780. His collected works were eventually published in 1798.

Condillac put forward a sensualist account of mental operations characteristic of his day (see, for instance, Hartley and Bonnet). But unlike many such thinkers, his account of them is not materialistic. Indeed, he accepted a dualist framework, in which, though mental operations corresponded to physical processes, they were not identical with such processes (just as a Turing machine can be described independently of its specific physical instantiation).

In the Essai sur l’origine des connaissances humaines (‘Essay on the Origin of Human Knowledge’), Condillac presents an empiricist account of knowledge, in the tradition of Locke. Indeed, the subtitle describes the work as a ‘supplement’ to Locke’s Essay. The basic building blocks are mental impressions. From these alone, provided that we allow them to differ in vivacity and agreeableness, we can show how attention, memory, pleasure and pain, reminiscence, comparison are produced. ‘All mental operations are nothing but sensation transformed in different ways.’ For instance, attention is nothing other than an impression standing out by virtue of its vivacity. Memory just is an impression which persists. Condillac, unlike Locke, does not distinguish between ideas of inner sense, which arise from awareness of what goes on within us, and ideas of outer sense which have their origin in the outside world. Furthermore, unlike Locke, he claims that language plays a constitutive role in the formation of ideas from impressions.

But if all impressions are nothing but modifications of the mind, and our awareness can be of nothing but these modifications, how can Condillac escape idealism ? He rose to this challenge, levelled by Diderot in his Lettre sur les aveugles (‘Letter on the Blind’) (1749), in the Traité des sensations (‘Treatise on Sensations’). Like Bonnet, he used the thought experiment of a statue presented only with sensations of smell, claiming that when a rose is presented to the statue, the statue, from its own point of view, unlike that of an observer, will just be the smell of the rose. The crucial thing about Condillac’s statue, which is organised inwardly like a human being, is that its soul has never received an idea before the thought experiment is carried out. Once again, as earlier, he showed how, by successively exposing the statue to appropriately chosen stimuli, we could cause its virgin mind, having no innate ideas, and no built-in faculties, to build up the full range of mental operations. But this does not yet rebut the charge of idealism.

Condillac tries to do this by next giving the statue touch. If the statue touches itself, there are two sensations of resistance. But if it touches something else, there is only one. From this experience is generated our awareness of the independence of the outer world. Where Locke had assumed the distinction between an inner and an outer world, by postulating two sources of ideas from the beginning, Condillac claims to generate it. And touch now becomes the tutor of the other senses, for instance training sight to give depth to the visual field.

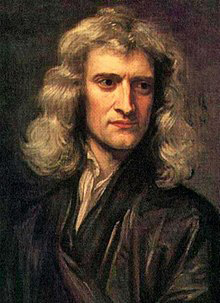

In describing this position, Maine de Biran, who admired and attacked Condillac, used the analogy of the infinitesimal calculus: Condillac had tried by ‘integration’ from simple sensations to arrive at the mind as we know it. This is a telling analogy, both physically and mathematically. Physically, because Condillac had another hero besides Locke, namely, Newton. Newton had famously said, at one point, that if the inverse square formula worked, there was no point in speculating about what gravity really was. This would be ‘metaphysics’ in the bad old sense. This is somewhat similar to Dirac’s much later claim in regard to quantum mechanics that it does not really matter whether or not we have an intuitive model to interpret the mathematics which ‘works’.

Condillac wanted a different kind of metaphysics which would have no occult forces and no inaccessible essences, and he found it by giving a new role to language. For language, as we have seen, was constitutive of ideas. And it began with ‘natural signs’, that is, items of behaviour which were naturally associated with certain kinds of experience. However, from this natural basis, he claims, we bootstrap ourselves into creating signs which are purely conventional, and which allow relations between them to be combinatorial rather than associative. It is thus that a language becomes ‘an analytical method’, that is, it serves to display the relations of the mental acts and elements corresponding to an utterance.

In his last work, posthumously published, he explored ideas which were precursors of logicism and finitism. Knowledge was a well-made language. Thus the development of any special science had to be manifest in the development of its language. And the criterion for its being ‘well-made’ would lie in its analogical conformity to the model of algebra. The language of later chemistry would be an illustration of this. Signs in algebra are the purest signs, because not only are they conventional, but also they have no specific reference. The propositions of algebra are the purest propositions, because they are tautologies. The special sciences must fit themselves to this model. Note that Condillac himself contributed to the early development of economics, in his Le Commerce et le gouvernement considérés relativement l’un à l’autre (‘Commerce and Government considered in relation to each other’). For here too is a discipline whose later development might be taken to illustrate Condillac’s requirements about developing a ‘well-made language’.

But, in spite of the constitutive role of language in the formation of ideas, it should not be assumed that every linguistic sign has a corresponding idea. For example, real numbers and complex numbers have signs, such as ‘√2’, ‘√-1’. According to Condillac, though these are legitimate signs in a calculus, they do not correspond to real ideas, since they cannot correspond to actual mental operations which could determine these numbers in the way in which the integers can be determined.

Thus, in his latest work, Condillac gave remarkable pointers to modern discussions about the nature of language in general, and of mathematics in particular, which make his ‘empiricism’ very different from that of the predecessors whom he expressly admired.

There is another reason for calling into question his ‘empiricism’, namely, his work Les Monades (‘Monads’). This early work was rediscovered and attributed only in 1980. No doubt, Condillac had his own social and intellectual reasons for keeping his authorship secret. This work could have been ‘misinterpreted’ (as he might have thought) as undermining his attack on traditional metaphysics. For although, in the first part, Condillac attacks the Leibnizians, and claims explicitly that we must start with ideas of sensation, in the second part, he gives a finitist argument for the existence of simple indivisible entities, i.e. monads.

It is interesting that Jacques Derrida, in his introduction to an edition of the Essai sur l’origine des connaissances humaines (‘Essay on the Origin of Human Knowledge’), an introduction which was originally published before Les Monades was identified as the work of Condillac), wonders whether ‘Condillac plagiarized Leibniz without knowing it’. What we now know is that, from the beginning, Condillac had a sense of the metaphysical reach of his ideas, and of their relation to those of Leibniz, which goes beyond (even if it does not undermine) his ‘official position’ about the rejection of traditional metaphysics.

In short, if Condillac naturalised empiricism in eighteenth century France, he did so in an unexpected way which opened unusual windows to future philosophers of language and mathematics, and to past metaphysics.

(1746) Essai sur l'origine des connaissances humaines, Mortier: Amsterdam

(1747) Les Monades, Proceedings of the Academy of Berlin (anonymous)

(1749) Traité des systemes, Neaulme: The Hague

(1754) Traité des sensations including Dissertation sur la liberté, de Bure: London and Paris

(1755) Traité des animaux including Dissertation sur l’existence de Dieu, de Bure: Amsterdam

(1755) Traité des animaux, de Bure: Amsterdam

(1775) Cours d’études pour l’instruction du prince de Parme, Imprimerie Royale: Parma

consisting of the following volumes:

1 Grammaire

2 Art d’écrire

3 Art de raisonner

4 Art de penser

5-10 Introduction à l’étude de l'histoire ancienne

11-16 Introduction à l’étude de l'histoire moderne

(1776) Le commerce et le gouvernement considérés relativement l’un à l’autre, Jombert et Cellot: Amsterdam and Paris

(1780) La logique ou les premiers développements de l’art de penser, L’Esprit et de Bure: Paris

(1798) Œuvres, revues, corrigées par l’auteur, imprimées sur ses manuscrits autographes et augmentées de la Langue des calculs, ouvrage posthume, Houel: Paris

Auroux, S & Chouillet, A-M (ed) (1981) La Langue des calculs, reproduction de l’édition de 1798, avec les variantes du manuscrit, une introduction et des notes, Presses Universitaires de Lille: Villeneuve d’Ascq

Bongie, L. L. (ed) (1980) Les Monades, The Voltaire Foundation: Oxford

Picavet, François-Joseph (ed) (1919) Traite des sensations, Première partie, publiée d'après l’édition de 1798, augmentée de l’extrait raisonné des variantes de l’édition de 1754, de notes historiques et explicatives, d’une introduction et d’éclaircissements, 4e édition soigneusement revue par François Picavet, Delagrave: Paris

Le Roy, Georges (ed) (1947-51) Œuvres, Presses Universitaires de France: Paris. Volume 3 is the first edition of Condillac’s Dictionnaire des synonymes, written in Parma.

Derrida, Jacques (1976) L’archéologie du frivole, Denoel/Gonthier: Paris (see Leavey, John P. (trans) (1987 <1980>) The archeology of the frivolous: reading Condillac, University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln

Hine, Ellen McNiven (1979) A critical study of Condillac’s Traité des systèmes, Nijhoff: The Hague

Knight, Isabel F. (1968) The geometric spirit: the Abbe de Condillac and the French Enlightenment, Yale University Press: New Haven

Le Roy, Georges (1937) La psychologie de Condillac, Boivin: Paris, 1937

Salvucci, Roberto (1982) Sviluppi della problematica del linguaggio nel XVIII secolo: Condillac, Rousseau, Smith, Maggioli, Rimini

Sgard, Jean (ed) (1982) Condillac et les problèmes du langage (Travaux présentés au colloque de Grenoble, 9-11 octobre 1980, pour le bi-centenaire de la mort de Condillac), Slatkine: Genève

Sgard, Jean (ed.) (1981) Corpus Condillac, Slatkine: Genève