As a boy, I was fairly religious. I was a choirboy in All Saints church in Sutton a couple of miles away from our home, and I used to cycle there. My parents did not attend it, preferring instead to go from time to time to St Lawrence’s, a strongly protestant church in Morden, near where Auntie Dora lived, where the pastor, the Revd Livermore, gave sermons denouncing ‘papism’ and all its works and manifestations.

I didn’t like the Revd Livermore’s tirades, because the church in which I was a choirboy was a high Anglican church where Father Donovan had implanted old rituals, chants and ceremonies. Some possibly predated the division between the Eastern and Western Church, let alone the rise of protestantism. On Good Friday we had the Liturgy of the Presanctified, which is probably of Eastern orthodox origin. At the end of this service, instead of processing solemnly back to the vestry led by the crucifer, we had to run off in all directions, representing the flight of the disciples of Jesus. This was good fun.

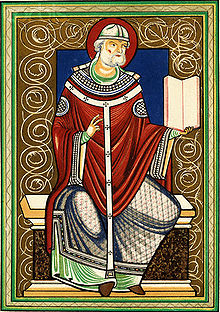

The Liturgy of the Presanctified may have been codified by Pope Gregory I in the sixth century.  Click here to see and hear part of this liturgy being performed in the Convent of the Ascension, Jerusalem (use the back button of your browser to return).

Click here to see and hear part of this liturgy being performed in the Convent of the Ascension, Jerusalem (use the back button of your browser to return).

In All Saints, we also prayed not only for the sovereign, and the Archbishop of Canterbury, but also for the Pope and the leaders of the Orthodox church. Obviously I had only a very vague idea of what all these things meant as a boy. Or perhaps even a Doctor of the Church does not really understand them any better than a child, for all his wit and learning. Or was Newton right ? He wrote: “ ’Tis the temper of the hot and superstitious part of mankind in matters of religion ever to be fond of mysteries and for that reason to like best what they understand least.”

It was decades later that I was told by Colin Davies, a Hong Kong friend, about the ‘filioque’ and the ‘eternal procession’ (St Augustine’s term, I think) which gave rise to the schism between the Eastern and Western churches. This came out of discussions about the Trinity. Though many early Christians shared a belief in One God, they also shared a belief in the paradoxical idea that this one God had three ‘persons’, Father, Son and Holy Spirit, being different ways in which He could act or be apprehended by humans, an idea for which they found a scriptural basis. But what was the relation between these three persons? Those who were to become the Westerners coined as an article of belief that the Holy Spirit ‘proceeded from the Father and the Son (“filioque”)’. This was anathema to the Easterners who perceived it as creating a sort of inequality between these aspects or forms or presences of the Deity. They thought that it downgraded the Holy Spirit.

The Revd Livermore, I think, would not have been much interested in these perspectives. Or perhaps he just knew where he stood, on the side of a faith based directly upon the text of the Bible (as translated into English from the Vulgate, being the Latin version of the original texts, made for the Western Church, mainly by Jerome in the fifth century AD), without intermediaries or embellishments, and especially without anything suggesting idolatry in general or Mariolatry in particular. He would have stood in the line of Cromwell. He would have deeply disapproved of a beautiful High Mass I attended in St Mary Magdelen’s Anglican church in Oxford on 31 October 2004, which was attended by people of many origins, including Japanese, Americans, Africans and so on, and concluded after the Mass itself by the Holy Mary, sung by the priest carrying a baby, divested from his vestments for the mass, and by the congregation.

The Revd Livermore abjured ‘bells and smells’. He would not have liked one of the three officiant priests going round the congregation, sprinkling holy water on them. Nor would he have liked the incense and the candles. He would have liked the sermon about the Sermon on the Mount or the Beatitudes (in which Jesus said that it was people such as the poor, the hungry, the distressed, and the despised who were blessed—and definitely not the bankers), which was clear, moving, unpretentious, and humorous. He would have repudiated the term ‘The Mass’, and especially ‘High Mass’. He might perhaps have liked the way in which the congregation sang various parts of the service in full voice, and in English. He would not have liked the fact that the choir sang parts of the service in Greek and Latin, despite — perhaps even because of — the beauty of their singing. I find it difficult to imagine how he would have coped with my Japanese neighbour in the pew. Or with the ‘Peace’, in which participants go round wishing peace to their neighbours, in the ancient Semitic fashion.

I remember one sermon of Father Donovan, though he gave it some sixty years ago. He viewed the sermon as an occasion for instruction. Nothing like raising enthusiasm or making moral injunctions or encouraging conversion to the faith. In that sermon, he tried to explain the notion of transubstantiation, and for some reason I was actually listening (I was perhaps ten or eleven years old). He said that the bread and the wine in the sacrament of Holy Communion actually became the very body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ, who had said, after all, at the Last Supper, ‘this is my body’ and ‘this is my blood’, when he distributed the bread and the wine to his companions at the supper. It is hard to think that anyone, even or especially a spin doctor, would have thought to invent that extraordinary saying after the event, or would have misremembered it. The most economical explanation is that Jesus did say it. But what could he have meant? (Click here for a discussion of the literal and the symbolic: about imperfectly understood beliefs.)

When I was fifteen or so I went with some fellow-pupils from my school to a meeting addressed by Billy Graham in south London. Though I did not feel at all sympathetic to his general position or style, when he asked ‘believers’ to stand up, I did so. The result was that I was segregated from my friends, and driven back separately, with a man in the back-seat of a car who kept giving me disagreeable pats on the thigh. I had apparently been converted. I acquired at that point a quite strong dislike of the very idea of being a ‘born-again’ Christian, thinking vaguely that I was already a Christian in my own way, and that this evangelist had not really made any difference to me, other than causing me to stand up in the stadium, and that I was not generally sympathetic to the idea of sudden conversion, despite the story of Saul on the road to Damascus. Maybe I already had some reservations about the role of St Paul in Christian history.

A few years later I became infatuated with an attractive young woman. She had been attending a wedding in All Saints, where I was still in the choir, and I met her on the pavement outside. Subsequently, she took me to a Baptist service, as a further step in our friendship. I did not share her taste in music. (It took the Beatles a few years on to open my ears to music beyond the classical canon.) Maybe I said to myself: ‘Never mind if she likes Hollywood musicals. After all she is a person with a lovely body, a cheerful temperament, and a gleaming eye.’ Anyway, I couldn’t really cope with the Baptist service. We lost touch with each other.

Around that time, I went to a lunchtime prayer-meeting at school. It was voluntary, and presided over by a cleric and teacher who later became the Headmaster of St Paul’s School in London. I was not sure what to do, and felt a bit uncomfortable. Apparently each boy present was expected to improvise his own prayer. I didn’t think much of those which came before me, because they seemed rather sanctimonious. When it came to my turn, this being at the height of the Cold War, I thought that we should pray for our ‘enemies’, in light of injunctions in the Gospels, so I explained that in a few words and offered a short prayer for the then leaders of the Soviet Union.

I meant it, in my immature thoughts, on my knees in front of a desk; I wasn’t trying to put on a show, but trying to take part in the activity at hand. Probably I did not believe in the efficacy of prayer, but rather thought that it was symbolic. Though in that matter, I cannot be certain what I thought when I was a teenager, and perhaps we cannot be certain what any ordinary person in any religion really thinks about the efficacy of prayer, other than that it is a required, appropriate and decent activity which places immediate concerns sub specie aeternitatis. Subsequently, the teacher asked me gently if I might want to become a priest like him. But I said no.

from this page you can print the

whole section, without illustrations,

hypertext references or

navigation tools

go on

— go back to the guide