But let us return briefly to the technology of writing. Writing was introduced to Europe by the Greeks, who adapted the Phoenician script (of which a sample is shown here on gold plate),

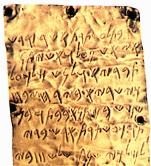

it consisted of a continuous stream of capital letters (scriptura continua). Here are two examples, the first a Greek loan contract of the first century BCE:

The second is the beginning of St John’s Gospel in the Vulgate (the Latin version of the Bible):

INPRINCIPIOERATVERBVMETVERBVMERATAPVDDEVME

TDEVSERATVERBVMHOCERATINPRINCIPIOAPVDDEVM

(Cursor over the beginning of the above text to see Augustine’s comment.)

Now there is considerable evidence to show that silent reading came surprisingly late in the history of European literacy. Note this well-known passage from the Confessions of St Augustine: ‘When [Ambrose] was reading, his eyes were led through the pages, and his heart sought out understanding, but his voice and tongue were silent.’ Manifestly, Augustine was surprised to see someone read silently.

The groundwork for silent reading was laid by the introduction of spaces between words in 7th century Ireland. This became normal in the British Isles, but did not spread to France and Italy until about the tenth century. Small letters and punctuation marks had also appeared by this time.

Silent reading became feasible, or at least much easier, and made it possible to ponder and interrogate a text in an inner world of reflection, rather than publicly. But teachers, instead of recognizing the potential (and perhaps the revolutionary implications) of a new technique for learning, saw it as dangerous. For if the student does not read the text aloud, how can the teacher know whether he or she is construing it correctly? There were strict rules against silent reading by students in the University of Paris as late as the fourteenth century.

The general issue which this interesting example raises is a perennial one: are the Universities doing their job? Are there jobs they are not doing now but ought to be doing? Are there jobs they are doing now but ought not to be? Do they see the implications of new technologies, or bury their heads in the sand, like the teachers in the Sorbonne prohibiting silent reading?

I look first briefly at the French response to this kind of challenge, which has typically been not so much to reform existing institutions as to multiply them. Here is a very small sampling of cases.

The first example is particularly interesting. It seems that even as late as the early sixteenth century, French Universities were still not teaching Greek. The King set up the Collège de France in 1530 for this (and for other subjects not pursued in the Universities) for research, and as an example of what we call today Open Learning. Lectures are (still today) freely open to all-comers; there is no enrolment, no curriculum, nor examinations, nor qualifications awarded. A chair in the college is among the most prestigious honours in French intellectual life.

The Académie Française was established in 1635 to protect and regularize the French language by producing authoritative dictionaries. The École des Beaux Arts was established in 1648 for training artists. Other schools were set up for training engineers (the École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées in 1747, and the École des Mines in 1783).

Revolutionary institutions included the École Polytechnique, founded in 1794. Napoleon soon made this a uniformed school. Today’s uniform is not a military one, but the school still falls under the Ministry of Defence, though it has a broad curriculum, covering mathematics, information science, mechanics, physics, chemistry, biology, economics, humanities and social sciences, languages. There was also the École Normale Supérieure established in 1794 for the training of teachers, and the Institut de France of 1795, covering four broad disciplinary areas, and intended to replace earlier Royal Academies which were thought to be affected by ‘the gangrene of aristocracy’. Later foundations included Sciences Po in 1872 for political science, Hautes Études Commerciales in 1881 for business, and the Centre Nationale de Recherche Scientifique in 1939, which has about 12,000 researchers, and a budget of about HK$16 billion (figures for 2000), and is responsible for 80% of France’s research publications. Areas of research covered are nuclear physics, physical and mathematical sciences, engineering science, chemical science, cosmology, life sciences, human and social sciences.

Finally, I mention the École Nationale d’Administration, created by de Gaulle in 1945 to form senior administrators. Typically, the ‘énarques’ account for about a third of cabinet ministers, senior civil servants and managers of large companies. There are also several recent institutions in the field of information technology. All these and others not listed here are élite institutions, with multiple links and joint ventures. They are autonomous (to varying degrees), independent of the University system, and are financed by at least twelve different ministries. Most of them, unlike the Universities, are very hard to get into. What we see in France, then, is a remarkable diversity of institutions.

Recently, we have seen the opposite response to such challenges to higher education, in Britain, Australia, and Hong Kong, for instance. Here the model is to strengthen the centralization of power (in our case in Hong Kong, through the University Grants Committee), to homogenize higher education, to introduce ‘market forces’ by creating a pseudo-internal market in higher education under which there is competition for resources, and to reform the institutions. I construe the UGC’s recent introduction of a centralized system to identify and fund ‘areas of excellence’ as a symptom of unease about this strategy in the bureaucratic mind.

Reform might have benefited by more hard thought and historical perspective about models for incorporating knowledge, and somewhat less attention to supposedly rational managerial structures and strategies, which are often the reverse of rational. In the end, only students themselves can incorporate knowledge in themselves, and it remains an ongoing question for our species how best they can be helped to do this. But I shall not attempt here to make an assessment of the pros and cons of the two models I have contrasted, partly because it would be too big a task, but mainly because events are overtaking us very fast. I refer to new technological developments which are likely to affect learning and research at least as radically as the invention of writing, or word-division, or printing.

No doubt, the most important of these is the World Wide Web. It is noteworthy that this was created in 1989/90 not in the USA, as one might have expected, but in Europe, and not for profit but, in the first place, as a free instrument for scholarly exchange between research scientists.

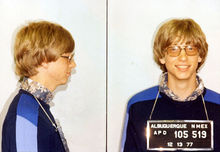

Even Bill Gates, who was prescient enough to be able to make an enormous fortune through software dominance in the field of computing, at first got things quite wrong on this point. When Web browsing began to be more common with the Web browser Mosaic, later to become Netscape (now itself defunct), Gates expressed the view that there was no future in the World Wide Web. It was somewhat later that he had to eat his words. (I remember noting this remark by Gates in the early 1990s, well before Internet Explorer was thought of, but I have not found documentation of it.

In fact, the commercial world was surprisingly slow to catch on to the advantages and potential first of the Internet itself, and later of the Web. Both technologies were intensively and widely used by academics before most businessmen had even heard of them. But now, things are very different.

Note that the following paragraph applied in 2000, and is now out of date. I have left it here in for interest, rather than updating it.

I take a random few of what must be hundreds of thousands of for-profit or non-profit institutions engaged in one way or another in online learning. Cisco has been actively engaged in this area for some years. Its CEO recently said that on-line education would make e-mail look like an accounting error. Cornell has recently set up e-Cornell. America On Line has joined up with Pearson, which claims to be the largest publisher in the world of educational material, and owns the Financial Times and the Economist. Pearson aims at 250,000 online students preparing for qualifications in a few years, and says that it wants to be world number one. ‘Portals’ are springing up daily, trying to persuade Universities to pay them a fee for listing their online courses. Meanwhile, just a month ago, Fathom was announced. This is a joint venture of which the founding institutions are Columbia University, the London School of Economics and Political Science, Cambridge University Press, the British Library, the Smithsonian Institution, and the New York Public Library. They plan to spend US$80M in the first year to set up ‘the premier site for knowledge and education on the Web’. The site itself will be free, though it may also provide access to fee paying courses at participating institutions. I include HKU in this section because I estimate that colleagues here have already put up at least a thousand learning sites or course Web sites. I believe that we need to address the issues raised by these developments urgently, to make sure that our students, wherever they may be, can have a good learning environment. This means, not abandoning traditional learning methods, but expanding them.

Some of these initiatives have retained the term ‘distance learning’. Let me explain why I think that this is a mistake. If there is a place where learning normally takes place, such as Plato’s Academy, the University of Bologna, the University of Oxford, the Sorbonne, the University of Hong Kong, a place where there are libraries, teachers, laboratories, and so on, then the possibility arises of devising ways in which people who are not in that place could be taught, at a distance from it. This challenge has been fruitfully met, world-wide, and not least here in the University of Hong Kong.

But what is coming into being with the Web is what Tim Berners-Lee, its creator, has called Universal Information Space: from the point of view of the user of the Web, there is no distance. Any document, wherever stored, may be just one click away.

This gives rise to various issues, and actual or potential conflicts, or different approaches. XML (among many other new possibilities) now allows the creation of documents of indefinite size which appear like one document to the user, but in which the contents may in fact be located in many different servers in the world, without being downloaded to a local server. Furthermore, in constructing such a document, one may insert one’s own links in materials incorporated from other sources, without modifying the source itself. Here we see ways in which the book, as something reasonably portable and not too expensive, may be transcended.

Corporations are rushing in, some to protect their rights or increase their profits, and some to increase the availability of knowledge (these objectives can be, but are not automatically, in conflict). Some want to expand intellectual property rights, others want to limit, or even abolish them. Xerox and Microsoft have just [NB this was written in 2000] formed a company to market a technology which will use XRML (Extensible Rights Markup Language), intended to allow those who have or claim rights in materials accessible through the Web to track (and charge the individual for) their use. At the other extreme, we see the Open Source movement. Linux source-code is free, of course: more interestingly, it was developed and debugged by hundreds of collaborators world-wide who belonged to no commercial organization for this purpose, and who worked on it without remuneration.

The long-term question is whether corporations like Universities or publishers will disappear. I would expect a period of creative confusion. Probably, the mixed-mode model represented by the Fathom initiative, or something similar to that, is a good way forward.

I now make a final more abstract point about the characteristics of Universal Information Space. Michel Foucault offered a well-known analysis of this painting by Diego Velázquez, Las Meninas. It is a picture of the women of the court of Spain, and we can see these women (together with a dog), and are well used to the representation of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional canvas.

But wait! At the left, there is an artist. Is it Velázquez himself? If so, what is he painting? Could he be painting the very picture which we are looking at? That would be strange ... But at the back of the room, we see a mirror with two indistinct figures. They must be the king and queen. But then it is we who are looking at the painting, so where are we situated, or where are the king and the queen? And what about the further space beyond the open door? Velázquez displays some paradoxes of spatial representation.

We return, finally, to the dimensionalities of information. We see that its aboriginal representation in human scripts was strictly one-dimensional. Irnerius’s glossing technology, and similar devices (such as parentheses, for instance), made it able to be two-dimensional. Henry of Renham’s copy-book is already a three-dimensional linking of texts. But Web documents with hyperlinks are potentially of unlimited dimensionality.

I find the possibilities of using this technology to create learning spaces very exciting (even though quite simply I also remain attached to — the book). There are new learning spaces, not only to be browsed, surfed or explored, but to be moulded and created, opening new possibilities for the incorporation of knowledge. That is today’s challenge.