(author’s note added in 2017: Re-reading this text over forty years after I wrote and delivered it, I find that the use of a metaphorical style of discourse in the opening pages is excessive, and that it is not clear what content this part of the paper has. But I decided to post a slightly modified version of the text here since the discussion of the relations between philosophy and social anthropology in the section entitled ‘a combative nexus’ may still be of interest.)

It is long since the social anthropologist was naturally conceived and desribed as a philosophical traveller. Not only has philosophy been much transformed since the eighteenth century, but the social sciences themselves did not really come into being until considerably later, and in a patchy way. However we have seen developed in these areas whole ranges of special techniques, vocabularies and rivalries.

Yet today we witness a curious and insistent phenomenon: a combative coalescence of the disciplines of philosophy and social anthropology, a rivalry compounded of mutual criticism and self-criticism, whether explicit or covert, multiple arrogations of authority over a disputed and problematic terrain. It is this phenomenon that makes today’s discussion of the philosophical implications and relevance of anthropology an appropriate and timely one. In this discussion there will be those who conceive of themselves as philosophers or as anthropologists, and who attempt to contribute to it from the distinctive vantage point of their own discipline.

Yet it is precisely the distinctiveness of these vantage points which is in question. For this reason, I am not only unable to contribute to it as an anthropologist (since I am not an anthropologist), but hesitant to contribute to it as a philosopher.

Let me rather make my main task an attempt to sketch that configuration of human knowledge which now bestows on anthropology and philosophy their mutually problematic situation; and if in so doing I am indebted to a number of philosophers, historians of science and anthropologists, let me not lay claim to the questionable authority that what I say is grounded in a particular discipline.

For what is it for a theory, an argument, a proposition to be grounded in a particular discipline ? or indeed, to be grounded at all? Wittgenstein wrote: ‘Giving grounds, justifying the evidence, comes to an end; but the end is not certain proposition’s striking one as true; it is our acting, which lies at the bottom of the language game.’

It will be our present task to characterize the Cartesian circle of knowledge of which this remark is a succinct critique, and to display the eclipse of that classical sun by the interposition of a dark body whose dubious outlines are confusedly emerging in and between the practice of philosophers and of anthropologists.

The Cartesian paradigm was generated by a trinity of notions: the ground, the way and the light. The ground is on the one hand the foundation of knowledge, that which provides the necessary support for knowledge considered as a static structure. It is on the other the starting point of knowledge considered as a process, a path, or a journey. The figure of the ground, then, is a crossover of two compelling metaphors, that of building and that of journeying. When we turn to the second notion, that of the way, it also appears in two forms; first, the way as a manner of proceeding, of covering the ground, as a ‘discourse;’ (for a discursus is a running to-and-fro), and secondly the way as a way to a particular destination, that which culminates in enlightenment, as a method, (for methodos means a following after something). It is no accident that Descartes wrote a ‘discourse’ on ‘method’. And the destination of his work is figured in the third generative notion: that of the light. But light is not only the destination of the way, namely, truth; it is also that which enables the ground to be evident, and thereby illuminates the way ...

It is these governing metaphors of ground, way, and light which articulate the analytic method, central to Western thought since Descartes. It is they which give a special place to intuition, that which determines the starting point of analysis: the intuition of which their founding axioms are for many mathematicians and logicians the purest expression; the intuition which marks what cannot be questioned in various species of philosophy, from linguistic analysis to phenomenology; it is the intuition which is described by Descartes as guaranteed by the natural light. It is these metaphors too which articulate truth as an absolute goal, and method as the means of attaining it.

And in constituting this space as the space within which intellectual travel must occur, they produce a central problem: there must be not only a common space but also a common place. Yet the commonplace is precisely that which must be called in question. As Descartes ironically indicates at the very beginning of the Discourse on Method, although good sense is the most fairly distributed of commodities in that no-one asks for more of it, yet the fact of human disagreement, even over matters which bring good sense into play, requires us to challenge what good sense seems to guarantee.

Yet the Cartesian circle prevents us from seeing that challenge through, in so far as the truth to which we aspire becomes in the end only the purification of an initial set of assumptions. It promises progress which turns out to be that of an inward spiral, along a path which, marked by parallels which, no longer Euclidean, are found not to promise endless and uniform advance, but to meet at the centre point of the vortex, an eye-point, a disappearing I of analytic truth where analysis plunges with increasing acceleration, a truth which is the other vacant face of the commonplace, a ground which, sucked towards the whirlpool, we discern to be only the notional bottom of a bottomless spout. We fall in.

Contrast the words of a still confident Cartesian at the beginning of the nineteenth century: ‘Without method the mind is immobile, and plunged in shadows. With a bad method, every step is a fall ... But if it is supported by a good method, everything changes. The mind emerges from the shadows which enveloped it: drawn on by the ever-growing impression of the light which it has glimpsed, it is gradually elevated; it rises from truth to truth, and, drawn by analogy to the source of light, it tastes at last the inexpressible pleasure of repose in the heart of evidence.’

We build and we progress. There may be bad constructions, but if found to be so they can be rebuilt in due course; there may be divagations, but, with Pilgrim, we may always return to the straight and narrow path. The paths, possible and actual, determine a landscape; the terrain provides natural foundations for what we build. We may always go on, and we may aways go up. Regions may be delimited, but they are regions of the one space. And the fixed axes of that space, its co-ordinates, are truth as a starting-point and foundation given by the natural light or by common sense, and truth as an absolute objective.

That space can be anchored only by two reference points: the inward point of reference, the solipsistic point of vision which is ultimately that of Cartesian self-consciousness, at which all that is, is self; and the transcendent standpoint, the unattainable but necessary vision of all reality as a geometrically disposed other. The classical dispute between rationalism and empiricism is made possible by, and is an expression of, this configuration of knowledge. According to it, human understanding becomes the analytic mapping, tabulation and representation of objects in Euclidean space. It is an external or an inward grid through which reality may shine.

But the science which was formed by and which flourished in the Cartesian circle has long since received three great and mortal blows which it is necessary to review before confronting our present predicament. These were the disruption of classical Euclidean space, the emergence of force as a possible object of enquiry, and the inverstion by which human understanding, no longer the transparent representation of reality, itself became a problematic object of investigation.

Classical space was disrupted definitively and explicitly by the discovery, or creation, of non-Euclidean geometries, and their fruitful application in the sciences, as in Relativity Theory. And this was not a development isolated to mathematics and physics. It marked a certain abandonment of the trancendental viewpoint, and consequently of Cartesian epistemology:

As Einstein was to Newton,

so was Wittgenstein to Kant,

and Malinowski to Frazer.

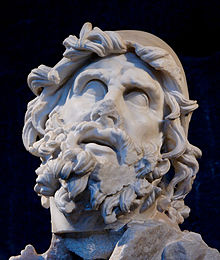

The nature of this geometrical revolution may be further indicated by contrasting classical space with the pre- Euclidean mythological world of which Odysseus was a denizen. His was not a world of the uniform possibility of travel between any two points; his space was not a space in which by uniform construction we might pass from one point to any other point. The whole story of his wanderings, the fact that he had to wander, is witness of that. It would be superficial to suppose that he happened not to know the way, that storms chanced to blow him off-course, that supernatural and extraneous agencies arbitrarily disrupted his natural return to Ithaca from Troy. It would be an error to think that the fabulous stopping-places on his journey were all on the same map — it would be still more absurd to try to identify on our maps the island of Calypso. For the mythical and bewitching quality of the tale of Odysseus is precisely that he passed through different worlds: that is, worlds which do not belong to the same space at all. What is magical in the Odyssey is not so much the fabulous scenes, events and personnages encountered at each landfall, but the very passage from one of these spaces to another. Odysseus passes from space to space though there is no intervening space. Thus the unity of his journeying lies not at all in the accidental fact that they are conducted as a continuous or irregular path through one space: they are not. It lies at first with the waiting Penelope: in her weaving hands, as the web grows and is unpicked again each day, and through that perfect figure, in the woven universe of the myth itself, the myth which by a semantics of its own weaves into one narrative diverse worlds of experience and imagination.

Thus Euclidean space was not always with us: nor it it any longer. And though the mutiple spaces of classical mythology are a far cry from the technically evolved multiple spaces in which and with which we can now operate, still we are like Odysseus in that the passage from space to space is today’s great crux: the passage from discipline to discipline (which is the topic of the present discussions), the anthropologist’s passage from one way of life to another; the passage of science from one paradigm to another.

The second blow to classical science was the emergence of force as a possible object of science. Where, for Newton, the names of forces were not to be the names of hidden realities, but terms of art denoting observed regularities of movement, for Einstein a description of a warping of space would be the description of a force. And so in a range of disciplines concepts which were now dynamic in more than a classificatory or Newtonian fashion came to the fore as did labour in economics, or the forces of the unconscious mind for Freud.

The third blow, and the most decisive from our point of view, was the coming of human understanding, of man himself, into the purview of science. This was, among other things, the birth of social anthropology. In the Cartesian configuration, what is important is to ensure that human thought starts from the right point, proceeds on the correct principles, and is directed towards the truth. So will it transparently represent reality. But with the disruption of that configuration, human thought becomes itself problematic. For before a proposition can be known, it must be able to be understoood. And for this possibility to be itself conceived, we must be able to understand understanding. What is it to understand? What is the meaning of thoughts, words, and actions which express or may seem to constitute our understanding? How can such things have meaning? What are relations of meaning?

Ernest Gellner in his book The Legitimation of Belief reacts with anxiety to what he calls ‘the meaning industry’, but when he advocates a mechanistic model of science, when he takes it as obvious that systematic conceptual boundary-hopping between disciplines is a misdemeanour, when he articulates the role of philosophy as that of a critical epistemology, we should recognize in him a nostalgia for that classical configuration of the sciences which has in fact disappeared. For Gellner is perhaps operating with the terms of a series of controversies whose conditions are still classical: controversies such as that between mechanistic and vitalistic views in biology, between positivistic and humanistic social science, between empiricism and rationalism. Classically, these disputes seemed irreducible and fundamental. Yet these rival views in fact sprang inevitably from the same conception of the enterprise of science. And when one who would still live in that lost world reacts to ‘the meaning industry’ as just the latest in a line of attacks upon true knowledge, as rationalism, vitalism or humanism in modern dress, he mistakes its real significance. He will be inclined to think of Peter Winch’s view of the social sciences as simply reactionary, of Thomas Kuhn’s view of the nature of scientific revolutions as a mere symbol of contemporary irrationalism.

But the real force of views like those of Winch and Kuhn is not that they are rearguard attacks on science, but that they are the symptoms of radical changes in the underlying conditions. Cartesian science emerged from Cartesian questioning of the possibility of knowledge: if we now question the possibility of meaning, we are in the midst of a new scepticism which marks a fundamental shift from classical science; as with Descartes Europe experienced a fundamental shift from Renascence thought, so appears a new scepticism (which finds, no doubt, its most uncompromising expression in the work of Wittgenstein) portending in its turn the emergence of a new configuration of science.

What this new form of science will be, if it will be, remains obscure, but the emergence of forms of structuralism in a variety of disciplines provides some clues. We may hazard that the following will prove to have been some of the decisive shifts:

— that which allows us to treat with rigour not only closed but open systems,

—the replacement of atoms as elements of analysis by structures as at least intrinsic to and perhaps as being our first data,

—the re-emergence of qualitative studies as a growth-point of knowledge marked by the emergence of topology as a crucial step forward from geometry as rendered numerate by Descartes,

—the view of knowledge as no longer constituted by an expanding set of autonomous disciplines to be related hierarchically, with philosophy as a sort of umpire, or to be regarded as irreducibly disparate, with their fracture lines marked by the emergence of what Jacques Monod did not hesitate to call ‘absolute coincidence’, and able to be linked only by dubious ad hoc exercises in interdiscipinarity, but as constituted rather by sets of specific articulations of disciplines upon each other.

And what may turn out to be the guiding metaphor? Perhaps that of nomadism (or transformation, of morphogenesis): the preservation of identity through travel, not in spite of it.

These remarks are bold and general. Many might regard them as foolhardy and vague. Let them at least provide some bearings to guide us in approaching that predicament manifested in the combative nexus between anthropology and philosophy of which we spoke at the outset.

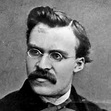

Philosophy, in turning to man, to human understanding, when man began to intrude into the field of scientific enquiry before the turn of the nineteenth century, did so in two distinct ways, after an apocalyptic announcement of the new situation in the work of Nietzsche: first, through a conception of human understanding as the form of thinking and speaking, a form to which psychological considerations were irrelevant — and this is the mainly Ango-Saxon tradition stemming from Frege to which logic is central; and secondly, through a conception of human understanding as the form of experiencing — and this is the European tradition of phenomenology, stemming from the work of Franz Brentano.

These schools of thought have been as fruitful as any philosophical tradition, but they have both suffered from an age-old vice. Western philosophy, since the moment of Socrates’s rejection of the natural sciences reported in Plato’s Phaedo has never ceased to construct defences against science, by attempting to discredit, modify or validate its findings on philosophical grounds, or — as a last resort — by attempting to secure an area as the proper preserve of philosophy, the enclosure taking a different form according to each advance of knowledge which philosophy, in this defensive guise, takes to be a new encroachment.

Thus we find philosophers, nomads whose title to land for grazing always yields, at least to some extent, to advancing sedentary communities which till the land and build upon it — we find them occupying temporary camps in various corners of the intellectual universe. The boundary of one such camp is marked by the notion of man as a free and conscious agent: here a central part of the study of man is supposed to be reserved for philosophy. The extreme version of this position was existentialism, of which Lévi-Strauss wrote, with some venom, but considerable acuteness, that it was

an exercise in self-admiration in which contemporary man is duped, shut up in colloquy with himself, prostrate in extasy before himself. It is cut off from scientific knowledge which is despised, and genuine humanity whose historical depth and ethnographic dimensions are not recognized, in order to set up a closed and private world: an ideological Café du Commerce where the habitués, safely inside the four walls of a human condition made to the measure of a specific society, all day long go over problems of local interest, beyond which the smoky atmosphere of their dialectical fug prevents them from seeing.

But the other camp is often marked by a stockade which may become as barren as the walls of the Café du Commerce, namely, the orthodoxy according to which philosophy is concerned with “conceptual problems”. On this view, the distinction between conceptual and empirical truths is taken to be axiomatic, and conceptual problems are held to be susceptible only to a specific kind of non-empirical investigation, that of the philosopher. “Descriptive metaphysics,” writes Peter Strawson calmly, “is content to describe the actual structure of our thought about the world.” Yet it is clear that he in no sense regards this as an ethnographic task. We might wonder whether ‘our thought’ is sometimes or somehow different from ‘their thought’ ...

At this point, as with phenomenology, philosophy finds itself back to back with anthropology. Human understanding becomes a natural object — a phenomenon for investigation. Philosophy, in her often fruitful response to this situation, has yet faltered, and slipped in a vain attempt to set this phenomenon outside nature once more, so that it might become that which has never existed, but which philosophers have constantly attempted to create, a pure philosophical problem.

It is time at last to turn from these generalities and to consider in some detail a specific example of the combative nexus between our two disciplines. Phew!

Wittgenstein wrote:

Imagine people who used money in transactions, that is to say coins, looking like our coins, which are made of gold and silver and stamped and are also handed over for goods — but each person gives just what he pleases for the goods, and the merchant does not give the customer more or less according to what he pays. In short, this money, or what looks like money, has among them a quite different role from among us. We should feel much less akin to these people than to people who are not yet acquainted with money at all, and practise a primitive kind of barter ... It is perfectly possible that we should be inclined to call people who behaved like this insane.

This is a revealing and apparently damaging passage. It suggests first the possibility of a purely internal investigation of any concept (such as that of money): that is, that anyone who has and uses the concept may, merely by sitting down and taking thought, give an account of it, without being called upon to give evidence of the correctness of his account (since empirical evidence is not supposed to be relevant to conceptual enquiry, except for purposes of exemplification); and it suggests secondly that any behaviour which is not intelligible in terms of the concept so defined, but which apparently should fall within its scope, can properly be regarded as insane. Do we not have here a conception of the role of philosophy as the privileged study of concepts, which I argue to be untenable — or only tenuously tenable — and a sort of contempt for empirical investigation of what people do and how they think, which is barren and potentially dangerous?

There are some parallels, for example, between Wittgenstein’s imaginary people, and the Rossel Islanders, whose use of shell coins has provided a crux for anthropological interpretation. One who observed, with Lorraine Barić,

the uncertainty of interest, the impossibility of expressing interest as an exact ratio of the principal, the impossibility of aggregating coins of different categories as equivalent to one of higher rank, the impossibility of saying that one category of coins was in any way a multiple or proportion of any other category’

would properly ask what concept of money is possessed by, or should be appealed to in understanding the economic behaviour of this people. No anthropologist, fortunately, would, with Wittgenstein, be “inclined to call people who behaved like this insane”, or, at least, any anthropologist would know to keep such an inclination in check, and try to understand what is going on. It is precisely the challenge for anthropologists to detect and neutralize in themselves the prejudices brought from their own culture which may impede understanding of another.

If this point is correct, it would have important consequences for any assessment of Wittgenstein's influence in discussions of the nature and functions of social anthropology, such as those of Peter Winch and Rodney Needham. It behoves us therefore to look at it more closely. We shall find that it does serious injustice to Wittgenstein.

Consider first Wittgenstein’s comment on our possible inclination “to call people who behaved like this insane”. Even in the case of his extreme example, he does not in fact approve this inclination, as our commentary has alleged. Consider how he goes on:

It is perfectly possible that we should be inclined to call people who behaved like this insane. And yet we don’t call everyone insane who acts similarly within the forms of our culture, who uses words ‘without purpose’. (Think of the coronation of a King.)

So far, then, from recommending the dismissal of his imaginary people’s monetary behaviour as “insane”, Wittgenstein hints that any tendency to do so would arise from an unthinking and misconceived attept to understand their behaviour in terms of our concept of money, rather than in terms of whatever rules govern and are specific to their way of life.

Thus Wittgenstein will be advocating the view that a practice can only be understood and justified within the context in which it is lived. Understanding of another society cannot be gained by coming into it with any set of assumptions from our own. The anthropologist should aim at being, as it were, an absolute nomad, one who takes no baggage along, who, in a new place, is a new person.

Yet this view, familiar from the work of Peter Winch, implying as it does a radical discontinuity between different ways of life, should preclude travel between them. At best one could imagine an abrupt, an irrational, a radical, an Odyssean jump from one to the other. And Wittgenstein has no remote Penelope to weave these travels into one web. Hence the besetting paradox of the ladder in his early work:

My propositions serve as elucidations in the following way: anyone who understands me eventually recognizes them as nonsensical, when he has used them — as steps — to climb up beyond them. (He must, so to speak, throw away the ladder after he has climbed up it.)

There is a similarly structured problem for the later work: for he has a position which empties its own key notion of content.

That notion is the notion of following a rule. Rules are intrinsic to and characterize ways of life. To understand a way of life is to understand the rules governing it, to know “how to go on”, to be able to “discourse”. Yet, it seems, these rules cannot be expressed except in so far as it is part of that way of life to enunciate them in certain circumstances. This view will make not only anthropology, but, in the end, all intellectual enquiry impossible.

The passage we have been discussing comes from the work called the Foundations of Mathematics, and mathematics, on Wittgenstein’s treatment of it will not only be deprived of various substantial branches, such as those flowing from the work of Cantor, but will also lose its admittedly problematic intelligibility. For Wittgenstein, “it is our acting which lies at the bottom of the language-game”. The notion of rule-following is fundamental, yet we are not allowed to give any general account of it. The moment that we do make such an attempt, we are being bewitched and misled by a picture that our practice seems to suggest. Like Odysseus, we may make many landfalls; but, unlike him, we may not unite them as episodes of return; it would be and illusion to say “However arduous the journey, our destination is the truth”: a dear and deep illusion indeed, but one which it should be the business of philosophy to dispel.

Here then is the new scepticism. Our strategy for overcoming it may be indicated by a return to the metaphor of the nomad which has been wandering through my remarks. The life of some nomads is characterized by their changing quarters according to the season. In many cases, one way of life belongs to and is imposed by the summer terrain, and another different one by the winter environment. But it would evidently be absurd to suppose as a matter of principle that the transition between these two ways of life must be arbitrary and abupt, since each could only be understood in its own terms. For the journey between the two is itself structured — and must be. Winter ways could not be understood independently of summer ways. To take a mundane but crucial example, summer may be the time for procuring and storing provisions for the winter.

Thus, very plainly, a central requirement of understanding a nomadic society will be the ability to account for its journeying in some way. This is the simplest example in which comparative ethnography is irreducible: for here one society comprises two forms of life (for example, two). The two therefore could never be taken as independent and autonomous objects of study. This remark is banal, but worth making, since criticism of the opposite extreme might lead us into a sterile sceptical position. We may illustrate such an extreme by taking an example characteristic of an older style of anthropology, in which wandering is treated as a global phenomenon. Ragnar Numelin, in a book entitled ‘The Wandering Spirit: a study of human migration’, began his study as follows:

There is a force which like a strong undercurrent runs through the history of all life. It is one of those deep, powerful forces which seldom stand out clearly but which are the more striking in their effect. Movement is the name of this force, and wandering is its biological manifestation.

He then proceeds to a systematic study of all forms of human and animal wandering. Without giving any detailed consideration to the argument of this work, we might today suppose on general grounds that its task is misconceived, in so far as it is committed to an assembling of what are surely essentially diverse phenomena. Such an initial doubt would be Wittgensteinian in spirit, and is perhaps justified; but we should not extrapolate from it to a total exclusion of comparative study. For all study, in some sense or another, is, or ought to be, comparative.

We may fruitfully return to the comparison between Wittgenstein’s imaginary money and the currency of the Rossel Islanders. It is true that this currency does not conform to Wittgenstein’s description of a situation in which there is no apparent regularity in the amount of money given over for goods. Yet there are important points of contact. For Wittgenstein’s case is one in which the function of money as a medium of exchange is rendered unintelligible by the elimination of something essential to that function, namely, there being some method of agreeing a price, but in a limited way a partial limitation of the price function is observed in the case of the Rossel Islanders, in so far as the different parallel currencies are not interchangeable. There is no exchange cross-rate.

Now Wittgenstein’s comments in his imaginary case should not be dismissed. There is an acuteness in them echoed in Mary Douglas’s comment (after Lorraine Barić), that the Rossel Islanders’ coins “are not currency in the strict sense”.

But Wittgenstein’s position suggests that we could do nothing other then regard their money and our money as belonging to quite disparate forms of life, of which we could only say: ‘These people go on like this’, and ‘Those people go on like that’. Douglas, by contrast, regards it as her task to search for a general reasoned account which could accommodate both sets of phenomena, which, however diverse, may yet be viewed as both being in some way economic phenomena. In other words, it is important for her to see whether there is a passage between an ‘advanced’ and a ‘primitive’ economy which would justify in a specific way the use of the term ‘economy’ in both cases.

The substance of her account is as follows. In any sufficiently developed economic system, we shall observe the need for two functions to be fulfilled: a monetary function which is aimed at facilitating a rather free exchange of commodities, and a rationing function with the function of controlling to some degree the distribution of commodities. Actual economic tokens, such as coins, she argues do not display either of these functions in pure form. It might be the nature of pure Platonic money to flow and circulate freely, yet the exchange power of all actual money is subject to, and partly constituted by primitive or sophisticated forms of exchange control. Conversely, ration coupons, though aimed at curbing free exchange, equally and inescapably acquire a tendency to perform monetary functions as well.

I believe that philosophers should be chastened by this example. Not only have they little to offer to anthropology, least of the claim that Winch seems to make, that anthropology really is or ought to be philosophy. But they should also learn that an orthodoxy underlying that claim, the orthodoxy according to which conceptual problems are the special preserve of philosophy, is an illusion. And if we ask what is the delimitation of the philosopher’s domain, my answer is that there is none, that more than any other are philosophers marked out for nomadism. This, perhaps, should not be view as a threat, but as a joy.

I do not know whether this doom has to be that of the dilettante, though I fear that much of what I have said today could be so characterized. But if the future of science is still dim in the uncertain outlines cast by the eclipse of the Cartesian light, how much more uncertain is the position of philosophy in that emerging configuration. Let her be admonished, if not led, by the work of the social anthropologist. Of this science, of its forms of sedentary or nomadic intellectual existence, I would indeed wish to speak. But I do not presume to do so any further. I have, for the moment, wandered — wandered perhaps too far.

Bachelard, Gaston, La Poétique de l’espace, Paris: PUF, 1957 (The Poetics of Space, trans. Maria Jolas, 1969)

Barić, Lorraine, ‘Some aspects of Credit, Saving and Investment in a “Non-Monetary Economy” (Rossel Island)’, in Raymond Firth and B.S. Yamey, Capital, Saving and Credit in Peasant Societies, London, 1964

Ludwig von Bertalanffy, General System Theory, New York, 1968

Brentano, Franz, Psychologie vom empirischen Standpunkt, 1874 (Psychology from an Empirical Standpoint)

Derrida, Jacques, ‘La Mythologie Blanche (la métaphore dans le texte philosophique)’, in Poétique, no. 5, Paris, Seuil, 1971 (translated by F.C.T. Moore, in New Literary History VI: 5-74, as ‘White mythology: metaphor in the text of philosophy’)

Descartes, René, Discours de la méthode (Discourse on the Method), 1637

Douglas, Mary, ‘Primitive Rationing: a study in controlled exchange’, in Raymond Firth (ed), Themes in Economic Anthropology, ASA Monograph 6, Tavistock 1967

Michel Foucault, ‘Les Mots et les choses’, Paris: Gallimard, 1966, translated as ‘The Order of Things’, Tavistock, 1970

Frege, Gottlob, Die Grundlagen der Arithmetik: Eine logisch-mathematische Untersuchung über den Begriff der Zahl, Breslau, 1884 (The Foundations of Arithmetic)

Gellner, Ernest, Words and Things, London: Gollancz, 1959; The Legitimation of Belief, CUP 1974

Gérando, Jean-Marie de, Considérations sur les diverses méthodes à suivre dans l’observation des peuples sauvages, translated with an introduction by F.C.T. Moore with a preface by E.E. Evans-Pritchard, Routledge Kegan Paul / University of California Press, 1969 under the title ‘The Observation of Savage Peoples’; reprinted in the Routledge Library Editions: Anthropology and Ethnography, 2004

Homer, The Odyssey

Kuhn, Thomas, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Chicago, 1962

Laromiguière, Pierre, Leçons de Philosophie, Paris 1815

Lévi-Strauss, Claude, L’Homme nu, Plon Paris, 1971; and ‘Comment meurent les mythes’ translated by F.C.T. Moore as ‘How Myths Die’ in New Literary History, V: 269-81

Monod, Jacques, Le Hasard et la nécessité: Essai sur la philosophie naturelle de la biologie moderne, Paris: Seuil, 1970, translated as Chance and necessity : an essay on the natural philosophy of modern biology, by Wainhouse, Austryn, London, 1970

Needham, Rodney, Belief, Language and Experience, Blackwell, 1972

Nietzsche, Friedrich, Die Geburt der Tragödie aus dem Geiste der Musik, 1872, (The Birth of Tragedy from the Spirit of Music

Numelin, Ragnar, The Wandering Spirit: a study of human migration, London: Macmillan, 1937

Piaget, Jean, Le Structuralisme, Paris, 1968, translated into English, C. Maschler, London 1971

Michel Serres, ‘Pénélope, ou d’un graphe théorique’, in Revue Philosophique, 1966

Strawson, P.F., Individuals: an essay in descriptive metaphysics, London: Methuen, 1952

René Thom, Stabilité structurelle et morphogenèse, Paris, 1972, translated by D. H. Fowler, W. A. Benjamin, Inc. 1976, Reading, MA

Wilamowitz (Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff), the attack on Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy for his “rape of historical facts and all historical method” is discussed in Wilt Aden Schröder, “Fünf Briefe des Verlegers Eduard Eggers an Wilamowitz, betreffend die Zukunftsphilologie! und die Analecta Euripidea”, Eikasmos 12, 2001, pp. 373f.

Winch, Peter, The Idea of a Social Science and its relation to philosophy, RKP: London, 1973

Wittgenstein, Ludwig, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, tr. D.F. Pears and B.F. McGuinness, RKP, 1961; Remarks on the Foundations of Mathematics, ed. and trans. G. E. M. Anscombe, Rush Rhees, G. H. von Wright, Oxford : Blackwell, 2nd edition 1967; On Certainty, ed. Anscombe and Wlar, trans. Anscombe and Denis Paul, Blackwell, 1969